CORS'ing a Denial of Service via cache poisoning

March 09, 2019

Since reading Practical Cache Poisoning by James Kettle, testing the misconfiguration of web caching layers for cache poisoning and other related vulnerabilities has become a standard go-to of mine when spending time on bug bounties or other pentesting activities. Recently, while doing some bounty work, I came across a potential impact of cache poisoning I hadn't seen before - one that left the Cross-Origin Resource Sharing (CORS) mechanism in browsers vulnerable to being abused by an attacker that could lead to a Denial of Service of the website being attacked. Unfortunately the asset in question was out of scope for the owner's bounty program because the site was hosted by a Wordpress-as-a-service provider, however it turns out this issue was more widespread than just the site I found it on, and possibly extended to many more websites hosted by the provider.

As a quick primer, CORS allows web resources to bypass the browser Same-origin policy in a controlled manner. Basically, it allows the Javascript on one site (e.g. ABC.com) to request an endpoint on another (e.g. XYZ.com) via fetch or XMLHttpRequest and read the response, if the resource being requested specifically allows it. I have previously posted about being careful not to configure CORS so sensitive data can be leaked, however CORS misconfiguration can also lead to denying access by abusing the access control mechanisms it provides. Take the following request, for instance:

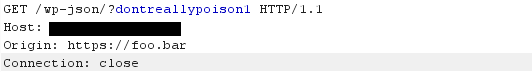

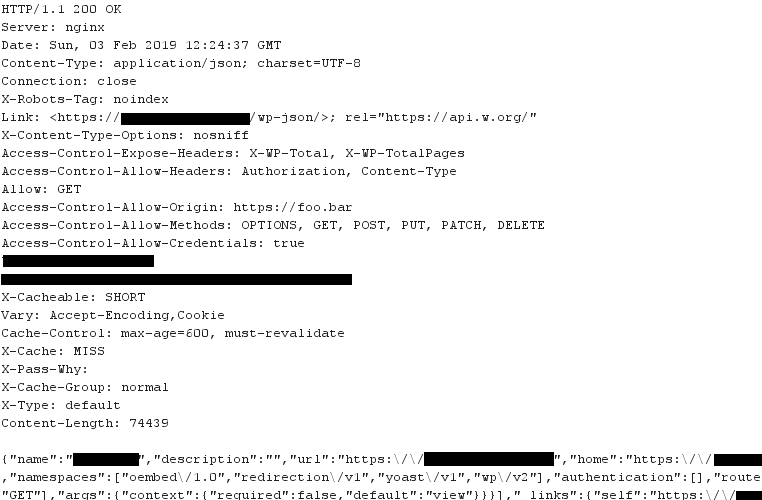

This condensed request is not very special - we're just requesting a WP-JSON API resource with a Origin value of https://foo.bar, which is just a dummy value to serve as an example of a different origin compared to the Wordpress site being requested. What does the response look like?

This is where things get a bit more interesting. As shown, our Origin value is now being reflected back in the Access-Control-Allow-Origin response header, which is the header that instructs the browser on whether the requesting origin is allowed to read the response. Given it is unlikely that https://foo.bar is specifically being white listed, it is safe to assume this means the response is just echoing back whatever Origin value is in the request. This echoing back is a rather common practice by web devs when trying to open up a resource to all origins, however it is not a good idea to do so without careful consideration, and in this case it will prove key to being able to abuse the CORS system.

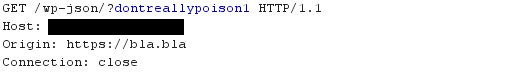

Other than the fact this echoing-back can be dangerous when the Access-Control-Allow-Credentials header is also being returned as true as outlined in my other CORS related post (although it appears WP-JSON may not be vulnerable due to requiring a valid nonce on all authenticated requests), this response hints at another problem - namely, the Cache-Control: max-age=600, must-revalidate in the response hints at the fact that this is a cacheable response. If there was some sort of intermediate web cache involved in this request, it may just cache it and serve future requests for this resource from cache. What happens if we request the same resource again, but this time change the Origin value in the request?

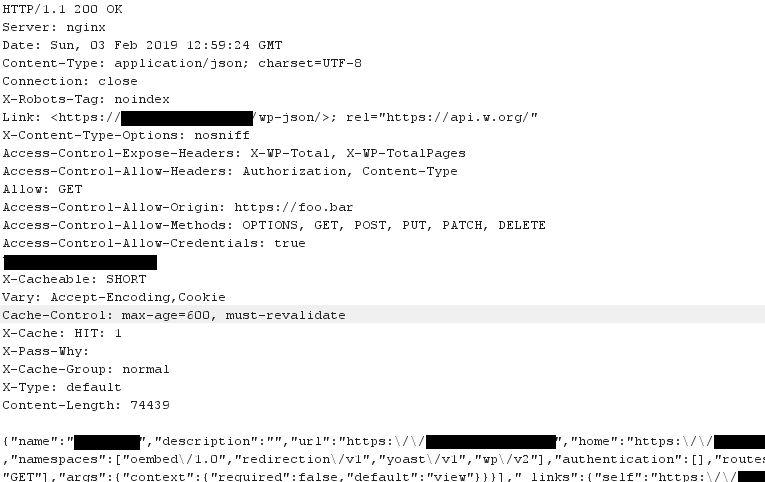

And the response:

We can see the response was indeed likely served from cache, as indicated by the X-Cache: HIT: 1 response header. This is where we can see the cache poisoning take effect. Despite the fact the Origin value was changed in the request, the response continues to only allow https://foo.bar read access to this resource in a CORS context. This is a classic case of cache poisoning as a result of something in the request being used in the response, but not being used in the cache key.

How does this lead to a denial of service? Well, consider the possibility that this Wordpress site is the backend of a "headless" or "decoupled" CMS style web app. In this approach, popular CMS' like Wordpress are used as content stores and content publishing interfaces, while custom frontends unrestricted by the CMS' theming engine are used as the presentation layer to the user, and communication between the two is often achieved via some sort of API and frontend Javascript framework pairing. What I have been requesting above is one such API, and it turns out Wordpress has had this REST-like JSON API (called WP-JSON API) inbuilt into its core package since v4.7, so you could say out-of-the-box Wordpress is ready to be used as a headless CMS.

If by some chance the frontend of the app in question happens to sit in a different origin than the Wordpress site (e.g. www.site.com for the frontend and api.site.com for the Wordpress instance), then the frontend would require CORS to be configured to allow it access to WP-JSON API, and this cache poisoning vulnerability could impact the availability of such an app, as the mismatch between a legitimate Origin value in a request compared to the attacker's poisoned Access-Control-Allow-Origin value in the response will result in an error like the following in a browser console:

This request should have worked, because we've already demonstrated that the backend is just echoing back the Origin in the Access-Control-Allow-Origin header, but what actually happened is this response was served from cache and the Access-Control-Allow-Origin value was poisoned by an earlier request. This of course would be the same if the Wordpress site wasn't being used in a headless config, but rather had other services on other origins that required access to the WP-JSON API, such as for content sharing purposes. Basically, this cache poisoning would affect any situation where WP-JSON and CORS are needed.

After reporting the issue, the Wordpress SaaS provider recently applied a fix that prevents requests with an Origin header from being served from cache.

Update 16/04/20: While it's not the report that originally inspired this write up, a similar report I submitted to Automattic for wordpress.com has been disclosed.